Salvatierra, Guanajuato, Mexico

November 14-15

One of Holly's friends told us that while we were in Mexico we should visit her grandparents in a little village called San Pedro de los Naranjos, near a town called Salvatierra in the state of Guanajuato. The possibility of a home cooked meal seemed like a good excuse to leave the highway. We departed San Luis Potosí and continued down Highway 57, the Mexican landscape changing again as we neared Querétaro. The dry plains turned into lush green farms, where fields were worked by everything from new industrial combines to horse drawn plows.

In Querétaro, we paid to take the Highway 45 toll road to Celaya . Five miles after we gave our toll, traffic ground to a halt. The highway was shut down for construction and we were diverted onto the “libre” road. As we sat idle in traffic, other drivers motioned for us to split lanes with our motorcycle. I wasn't sure what the law was, but we did it any way, slipping through the jam and onto the exit ramp. Other vehicles were courteous, allowing us back in when we had to merge onto the free road. In Celaya , we headed south on Highway 51 to Salvatierra.

It was in Salvatierra that we encountered our first “topes,” Mexico 's answer to traffic speed control. Made out of pavement, concrete, cobble stones or raised steel balls, the speed bumps added a new twist to Mexican driving. They were usually found leading into or out of small towns. Highway construction workers would even lay temporary ones out of dirt and gravel. Some were well marked. Others were not and could appear as a surprise, especially at night. One moment of distraction could lead to a bone jarring experience. I was glad I had changed the stock fork springs for Progressive ones in the Guzzi's front suspension. I developed a technique of braking hard to slow down and then letting off the brakes so that the forks could uncompress to deal with the tope. After the front wheel was across, a little more front brake would slow the bike down before the rear wheel reached the tope. Because the Guzzi's long suspension travel handles the bumps better than cars or trucks, we often used the topes as an opportunity, passing other vehicles as they almost slowed to a stop.

So far, our Mexican driving experience was a good one. Mexican traffic was like driving with a million Herbies, as white VW bugs fill the roads. Trucks are also popular, with Chevrolets seeming to be the brand of choice. It's best to approach traffic laws as suggestions. I stopped signaling to pass, especially in traffic, because we found that a signal indicates that it is safe for the car following to pass you. Though specific zones are marked for passing, drivers pass anywhere and everywhere, including over hills and around curves. I used hand signals and the power of the Guzzi's engine to get out and around other vehicles as quickly as possible.

We had stayed primarily on main highways, where the pavement was good and the lanes and exits well marked, but our deviations on side roads had been fun as well. Here the pavement was less predictable, roads and lanes were often unmarked and the cows and horses tethered by the road sometimes became untied and wandered onto the pavement. But the scenery was beautiful and the curves a welcomed relief.

San Pedro is a few miles further down the road from Salvatierra. The directions given to us were, “Turn right at the cantina and it's the second house on the right.” San Pedro, like many Mexican villages, must have a hundred cantinas. We asked around, without success. No one knew the couple named Lupe y Lupe.

| |

In San Pedro de los Naranjos we were directed to look for Holly's friend's grandparents at a town meeting that was being held up the hill near the church. Men with cowboy hats gathered in the street to hear el presidente of the town speak. After asking several by-standers who then asked several other people and with darkness approaching we gave up the search for Lupe y Lupe. |

With darkness already settling in, we headed back to Salvatierra to find a place to stay for the night. We hadn't planned to stop there and the town wasn't listed in our guide book, so we didn't have a clue of where to start looking. I wanted to stay in a little rundown motel we passed on the edge of town called El Mexicano. Holly insisted we head downtown, where we could see the lights of a church steeple above the low houses. Using the steeple as a beacon, we navigated cobble stone streets in that direction.

Holly's insistence paid off. We parked in a main square and I stayed with the bike as she looked for a hotel. She came back smiling and told me she had found a place down the street called the Hotel Cuauhtemoc. Its owner, a jovial short man named Juan Manuel Ornelas, allowed us to park our motorcycle in the courtyard. Juan owns a Japanese-made scooter and was fascinated with our motorcycle. He asked a million questions as we unpacked the bike. He wanted to know how much the Moto Guzzi cost and I told him, adding “Pero no tengo un coche (I don't own a car).” I don't own a car either, Juan said, patting his scooter.

Conversations in Spanish are working well for us. We were surprised by the lack of bilingual signs or English speakers in a country that relies heavily on foreign tourism. Most people take one look at me with my fair skin and light hair and direct their questions to Holly. But my attempts at conversation have paid off.

| |

The courtyard of Hotel Cuauhtemoc where we stayed in Salvatierra. The owner let us park the bike safely inside the locked gates of the courtyard, next to his scooter. |

| |

The trees around a small park in Salvatierra had their trunks painted white. We never found out the significance of this although it looks kind of haunting at night. |

We were the only guests at the Hotel Cuauhtemoc. The Spanish once stayed here, Juan told us and the building looked as if it has not been renovated since they left. But the tiny rooms were clean and neat and Juan fired up the gas water heater so that we could have hot showers. Dinner was at a restaurant recommended by Juan and equally deserted. Like the hotel, our host was happy to have us and she recommended that we visit the Templo de San Juan during our stay in Salvatierra.

Early the next morning, we made our way to the 18th century church. We found it on a narrow side street, its façade and surrounding fence decorated with fruits and vegetables, as part of an annual celebration to honor “El Señor del Socorro.” A crucifix is the central object in each decoration.

| |

Swags of fruits, vegetables, breads and lights adorned arches near the Templo de San Juan in Salvatierra. |

| |

The bell tower of the Templo de San Juan . |

| |

Three decorated arches were constructed along the street leading to the Templo de San Juan in Salvatierra. |

| |

Two old men sit by the Templo de San Juan Tuesday morning. |

| |

"El Senor del Socorro" is honored with colorful displays of fruits, vegetables and breads. At night, lights weaved into the offering lit up the arches. |

| |

El loro se llama Guero. Juan had several birds in the courtyard, including Guero, his parrot who had been enjoying a sweet tangerine for breakfast. |

| |

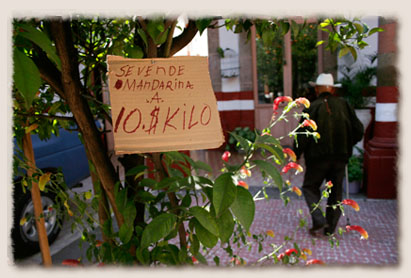

Juan was selling the tangerines off a tree in the courtyard of his hotel. Ten pesos is less than one U.S. dollar for about two pounds. |

Before leaving Salvatierra, we took our pictures with Juan, the Guzzi and his scooter. As we stood beside him he put his arm around our shoulders, and offered the camera a wide gold-toothed smile. He wished us luck on our travels as he held the gate open for our departure.

| |

Two men with one common love: their motos. Jeremiah gets a squeeze from Hotel Cuauhtemoc owner Juan Manuel Ornelas before we head out of Salvatierra. |

|

|